Rituals provide a nameable container for managing transformation and making meaning.

Nameable container

By assigning a name to a well-defined activity, a ritual allows people to point to a situation in need of navigation, and call for a specific response. This lets people use rituals to …

- Focus intentions

- Reduce the effort required to seek support

- Give permission to ask for support

- Establish expectations about intent and results

- Help marshal a community around a situation

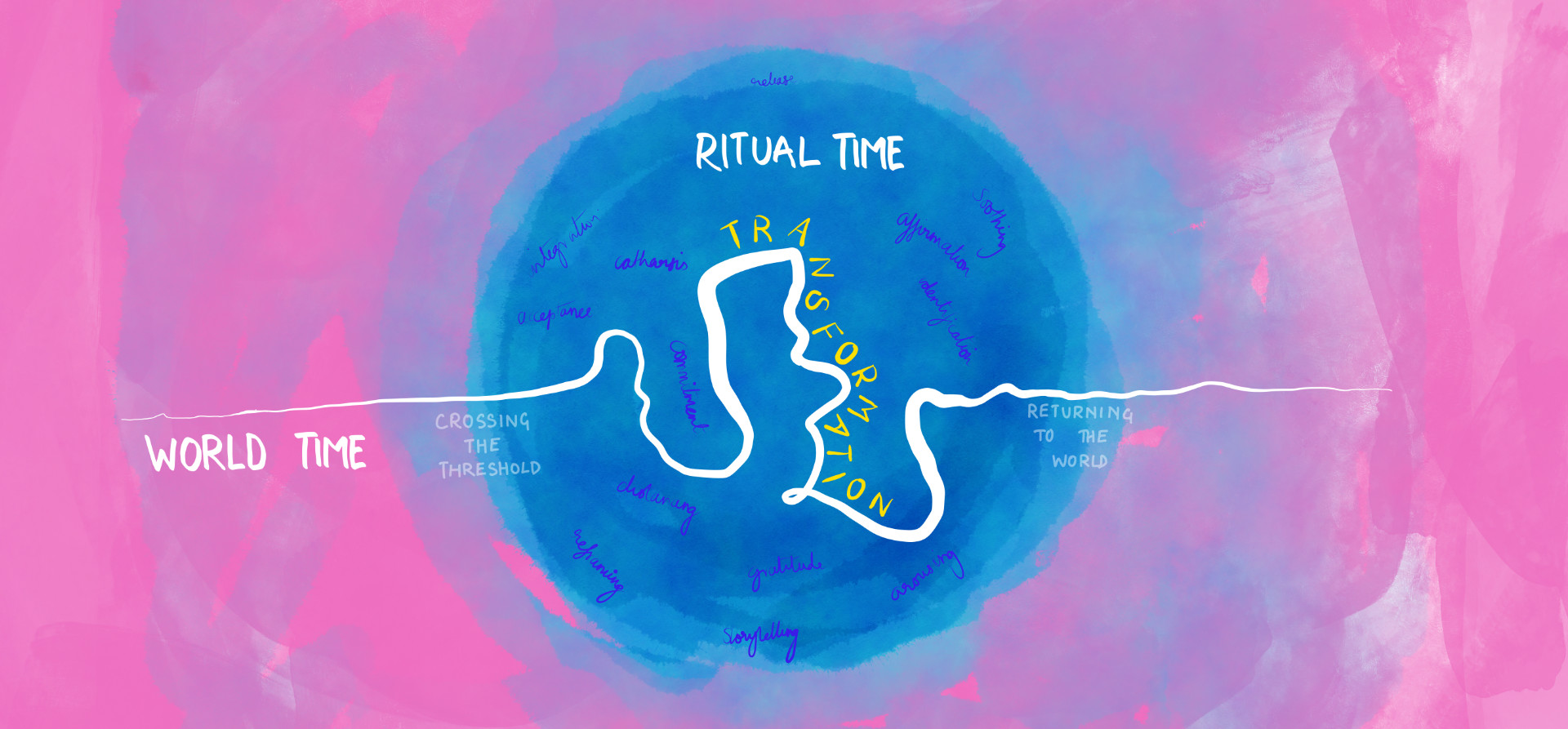

The container works by creating a separation from the every day world and the liminal space in which change takes place. In the anthropological literature, this separation of spaces is called “tripartite diachronic”.

tripartite diachronic means…

tripartite: three parts – world time, ritual time, and back to world time

diachronic: two kinds of time: world time (the everyday), ritual time (the liminal)

Sometimes this separation of spaces is physical — for instance, religious spaces dedicated to the sacred — but it can also happen through invocation, by merely taking actions or saying things that mark a separation from the usual everyday ways.

The effect of either is to allow people to change perspective.

Managing transformation

Rituals help provide structure to a process of transformation. Modern culture treats a huge variety of problems as ones to be solved on an individual scale. This can make changing oneself feel like an uphill task when not supported.

By using a ritual to effect transformation, the transformation becomes visible, and helps make it accountable. Other people can participate in the change, even if only to observe and reflect, making a successful response more likely.

Making meaning

By bringing people and energy to a situation, rituals can create felt experiences that can be meaningful and memorable. Emotionally engaging experiences help transformations stick, and provide a reason for people to return to them.

These experiences can also then lend significance to stories that originate from outside the ritual and link the individual, or a community, to the values and intentions of a broader culture. This is how most “traditional” rituals – especially religious ones – work. They bring a story to life, renew it, and connect people to it.

We can also create and reference our own stories, and build new community-scale culture through this work. The ritual becomes an activity with purpose and as long as it helps form or sustain a community, it feeds its own existence.

Ultimately, rituals are culture-generating machines.

More reading and resources

While we build out the website, you can read more about how we define rituals and what people have learned from studying rituals starting at page 7 of the Guide to the Ritual Design Toolkit.

Frameworks

Joanna Macey’s the Work that Reconnects

Books and other reading

Other ritual design approaches

Crafting Secular Ritual: A Practical Guide by Jeltje Gordon-Lennox (Author)

Rituals for Work: 50 Ways to Create Engagement, Shared Purpose, and a Culture that Can Adapt to Change by Kursat Ozenc and Margaret Hagan

The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why It Matters by Priya Parker

Anthropological studies of ritual

Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2004. Early Adulthood: The Winding Road from Late Teens Through the Twenties. New York: Oxford University Press.

Seligman, A. B., Weller, R. P., Puett, M. J., & Simon, B. (2008). Ritual and Its Consequences: An Essay on the Limits of Sincerity (1st edition). Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Bell, Catherine. (2009). Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice (1st edition). New York: Oxford University Press.

Bell, Catherine. 2009. Ritual: Perspectives and Dimensions–Revised Edition. Reissue edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Beck, R., & Metrick, S. B. (2009). The Art of Ritual. Berkeley, CA: Apocryphile Press.

Driver, T. F. (2006). Liberating Rites: Understanding the Transformative Power of Ritual. North Charleston, S.C.: BookSurge Publishing.

Turner, Victor. 2001. From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play. New York City: PAJ Publications.

Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure

Connerton, Paul. 1989. How Societies Remember. First Edition edition. Cambridge England ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Descent to the Goddess: A Way of Initiation for Women by Sylvia Brenton Perera.

Rituals in modernity

Cann, Candi. 2014. Virtual Afterlives: Grieving the Dead in the Twenty-First Century. Lexington, KY: The University of Kentucky Press.

Furstenberg, Frank F., Ruben G. Rumbaut and Richard Settersten Jr. 2005. “On the Frontier of Adulthood: Emerging Themes and New Directions.” Pp. 3-25 in On the Frontier of Adulthood: Theory, Research and Public Policy, edited by R. A. Settersten, F. F. Furstenberg, and Rubén G. Rumbaut. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Mesmer, S. (1455178870). All Praise the Women of Menopause. The New York Times.

Davis, Simon. 2015. “How Secular Americans are Reshaping Funeral Rituals.” Religion News Service, December 17. Retrieved February 25, 2016

Psychology and other ritual elements

Chaplin, L. N., John, D. R., Rindfleisch, A., & Froh, J. J. (2018). The impact of gratitude on adolescent materialism and generosity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 0(0), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1497688

Articles

A Design Lab Is Making Rituals for Secular People. The Atlantic. May 7, 2018. By SIGAL SAMUEL.

Ehrenreich, Barbara. “Capitalism launched a global campaign against festivities and ecstatic rituals”.

Conversations, Podcasts, and Videos

Tippet, Krista. Interview with Peter Berger, originally broadcast October 12, 2006, on “Speaking of Faith”.

Websites, reference collections

Daily Practices at Grateful Living